Enforcement of Tobacco Control

Laws In Ethiopia

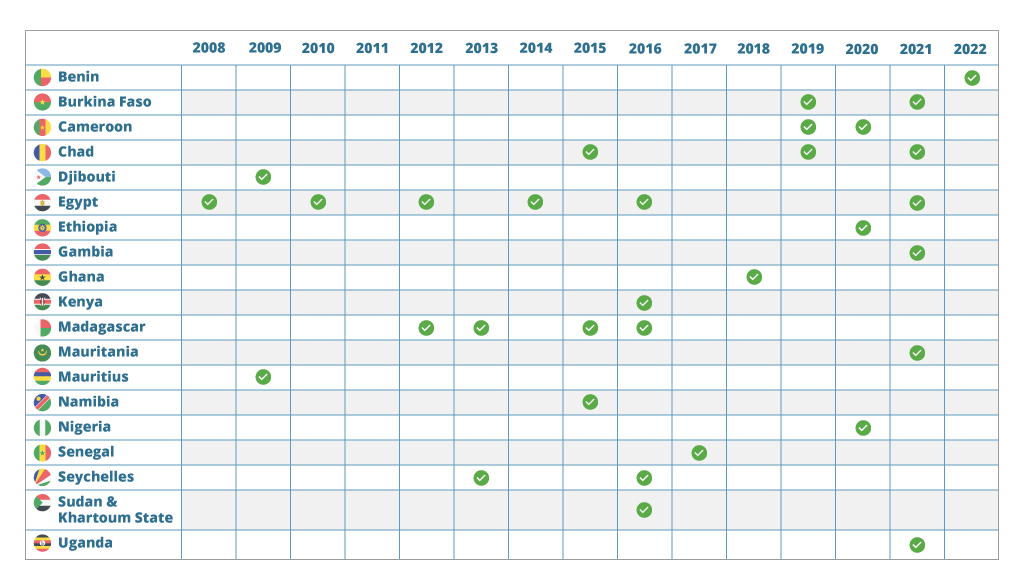

Ethiopia has one of the strongest tobacco control policies in the continent. It ranks 18 out of 206 countries worldwide that have implemented pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs.

There is fairly high compliance with Smoke-free and Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship (TAPS) laws. 76% of indoor hospitality venues and 70% of outdoor venues complied with smoke-free laws while 97% of outdoor points of sale and 60% of indoor points of sale complied with TAPS ban.

Enforcement capacity, stakeholder coordination, awareness level on harms of tobacco use and tobacco control laws need to be enhanced, both at the federal and regional levels.

Ethiopia signed the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) in 2004 and ratified it and came into force in 2014.

The WHO FCTC is the first international agreement to address the issue of tobacco use and tobacco control laws. The adoption of national laws is only the first step of domestication; the next challenge is enforcing these laws and ensuring that those subject to them comply.This page provides information on enforcement

of and compliance , in line with WHO definitions, with existing tobacco control laws in Ethiopia. The page also highlights the barriers and challenges with enforcement. We have referenced two studies conducted by Development Gateway in collaboration with Addis Ababa University (School of Public Health) and EFDA on compliance with Smoke-Free Laws and Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship ban and secondary data. The key stakeholders in tobacco control, along with their roles, have also been highlighted.To access the summarized results of the studies, please download the SFE factsheet here and the TAPS factsheet here.

Ethiopia has adopted various tobacco control laws to fulfill its obligations under the WHO FCTC, as outlined in the timeline below.

Tobacco Control Laws in Ethiopia

Prior to 2004, the legislative measures adopted by the Ethiopian government aimed to monopolize the tobacco industry rather than protect the public from the dangers of tobacco use and exposure to tobacco smoke. In 1942, the Tobacco Regie (Proclamation No. 30/1942) established a state monopoly to prepare, manufacture, import, distribute, and export tobacco products. This proclamation was repealed in 1980 by Proclamation No. 197/1980, which established the National Tobacco and Matches Corporation and gave the state the power to exclusively grow and process tobacco in Ethiopia. In 1999, the monopoly right of the National Tobacco Enterprise (NTE) was transferred to the National Tobacco Enterprise (Ethiopia) Share Company under Proclamation No. 181/1999. This monopolization of the tobacco industry by NTE was justified by the need to streamline tax revenues and boost employment opportunities.

Ethiopia has since made substantial progress in implementing tobacco control measures, by ratifying the FCTC through adoption of Proclamation No 822/2014 which gave the Ethiopian Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Authority (FMHACA) the mandate to implement the WHO FCTC. The most recent law, Proclamation No. 1112/2019 adopted in 2019, is a significant milestone in the country’s public health policy.

Major Tobacco Control Articles in Proclamation No. 1112/2019

Key Stakeholders in Tobacco Control

Article 5 of the FCTC mandates a comprehensive multi-sectoral approach to the implementation of tobacco control measures. It requires high-level political commitment and a whole-of-government approach.

The Ethiopia Food and Drug Authority (EFDA) is the main agency responsible for tobacco control policy development and implementation in Ethiopia, accountable to the Ministry of Health. EFDA is a regulatory agency at the federal level. As outlined below, other agencies and organizations bear responsibilities related to tobacco control. At the regional level, regional regulatory bodies and other departments are mandated with similar responsibilities in their respective regions.

Tobacco Control Actors and Their Roles

Source: EFDA, Ethiopia Tobacco Control Draft Strategic Plan 2015-2023 E.C(2023-2030/31)

Key stakeholders, including relevant ministries, civil society organizations and agencies, have been selected to establish the National Tobacco Control Coordinating Committee that oversees the implementation of the WHO- FCTC. A sub-committee called the National Tobacco Industry Monitoring and Response TEam has also been established under the National Tobacco Control Coordinating Committee.

Proclamation No. 1112/2019 prohibits smoking and the use of tobacco products in all indoor workplaces, public places, modes of transportation, and common areas. Smoking is also prohibited in all outdoor areas of healthcare facilities, educational institutions, amusement parks, and youth centers.

The Proclamation further prohibits smoking or tobacco use in any indoor or outdoor area within 10 meters of any public place or workplace doorway, window, or air intake mechanism. The Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) study assessed compliance with the ban on smoking in public in indoor

and outdoor hospitality venues . In this study, seven indicators were used to assess indoor compliance, while four indicators were used to assess outdoor compliance.Compliance With Smoke-Free Laws by Hospitality Venue

In the 2022 TCDI Ethiopia study

, overall, compliance with smoke-free laws is fairly high in Ethiopia. The average compliance with smoke-free laws by indoor hospitality venues was 76.18%, while compliance by outdoor hospitality venues was 70.45%.Indoor and Outdoor Venues’ Compliance with Smoke-Free Laws by Hospitality Venue, 2022

Source: TCDI Ethiopia Smoke-Free Study, 2022

As previously noted, several indicators are used to gauge a hospitality venue’s compliance with tobacco laws. The absence of a designated smoking area is one such indicator that has a high degree of compliance, with 98.2% of indoor hospitality venues and 96.4% of outdoor venues not having such areas. Similarly, the absence of ashtrays is another indicator with a high level of compliance – 94.8% of indoor venues and 98.8% of outdoor venues did not have any ashtrays. Conversely, compliance with tobacco control signage was low, with only 33.1% of outdoor hospitality venues and 35.2% of indoor venues having ‘no smoking’ signs on display.

Cafes and restaurants, hotels, and butcher houses & restaurants were the hospitality venues with the highest level of compliance with smoke-free laws. Nightclubs and bars had the lowest level of compliance.

Compliance With Smoke-free Laws by City

Indoor hospitality venues in Jigjiga and Addis Ababa had the highest level of compliance with smoke-free laws, whereas outdoor venues in Bahir Dar and Addis Ababa exhibited the highest level of compliance with these laws.

Compliance of Indoor Hospitality Venues with Smoke-Free Laws by City, 2022

- Compliance level|

- Fair 60-69%

- Good 70-79%

- Very good 80-100%

Source: TCDI Ethiopia Smoke-Free Study, 2022

Different cities had varying levels of compliance to smoke-free laws. Indoor hospitality venues in Jigjiga, Addis Ababa, and Harar recorded the highest level of compliance at 84%, 79%, and 79% respectively. Meanwhile, indoor venues in Dire Dawa had the lowest average compliance level, at 67%.

Indoor hospitality venues within five cities (Addis Ababa, Jigjiga, Dire Dawa, Harar, and Gambela) had 100% complied with the ‘no designated smoking area’ requirement. Indoor venues in Adama had a slightly lower – but still strong – compliance level (91.7%). Overall, the hospitality venue with the lowest level of indoor compliance was nightclubs/ lounges at 58% followed by bars at 61%. The nightclubs in Hawassa and Dire Dawa were the least compliant, while those in Addis Ababa had the highest level of compliance at 71%.

On the other hand, outdoor hospitality venues in Bahir Dar had the highest levels of compliance with smoke-free laws. No ashtray seen was the best performing indicator for outdoor compliance. Seven cities recorded 100% compliance, with only Addis Ababa recording the lowest level of compliance (at 96.4%). Semera-Logia and Hawassa had 99.1% and 97.3% compliance levels, respectively. However, no smoking sign was the worst performing indicator with only 8.3% of indoor venues in Jigjiga having any signs at all while 66.7% of indoor hospitality venues in Semera-Logia complied with the no smoking sign.

PM2.5 in Addis Ababa

76.4% of hospitality venues had moderate to good air quality. Air quality was poorest in nightclubs/lounges and bars.

Comparison of Indoor PM2.5 Concentrations ( µg/m3 ) of the Venues With Standard Air Quality Index Breakpoints

Observed Active Tobacco Use in Hospitality Venues

Indoor PM2.5 Concentrations ( µg/m3 ) in Addis Ababa, 2022

Source: TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022

PM2.5 is defined as particulate matter with a width of less than 2.5 µm. The study

goal was to measure the mass concentrations of particles with sizes ranging from 0.5 µm to 2.5 µm, which indicate secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure. Only 144 hospitality venues in Addis Ababa were analyzed for indoor PM2.5 concentrations (µg/m3). The majority (88.9%) of venues had indoor facilities, while 11.1% had both indoor and outdoor facilities. Among these venues, there was active use of tobacco products in 48% of bars, 45.5% of nightclubs, and 43.8% of grocery shops. The sampled restaurants did not record any use of tobacco products indoors, while cafe & restaurants only recorded 6.7%. As a result, the average use of tobacco products indoors in Addis Ababa was 29.2%.As a result of the seemingly low use of tobacco products indoors, 76.4% of venues had moderate to good PM2.5 concentrations (40 µg/m3 and below). Around 11% of venues had PM2.5 values that were unhealthy for sensitive groups (40.1-65.0 µg/m3), while 10.4% had values unhealthy for all groups (65.1-250 µg/m3). The air quality in two restaurants and one nightclub/lounge was hazardous (PM2.5 >250 µg/m3). While active smoking was not observed in restaurants during the study period, studies indicate that SHS remains in the air for a considerable period after smoking a cigarette.

This could explain why two restaurants had hazardous air quality.Interestingly, 30.7% of bars and restaurants had unhealthy air quality (over 40.1 µg/m3), even though only 25.6% of them had active tobacco use indoors. In comparison, only 27% of nightclubs/lounges had unhealthy air quality, despite active tobacco use indoors in 45.5% of them.

Proclamation No. 1112/2019 prohibits direct and indirect TAPS. This includes any commercial communications by the tobacco industry intended to promote a tobacco product or tobacco use, including the use of product packaging to promote tobacco products, and the open display of tobacco products. The TCDI Ethiopia study

assessed compliance with the TAPS ban at the point of sale (PoS).Overall, 96.5% of outdoor

PoS complied with TAPS requirements, compared to 60.3% of indoor PoS. Based on the interviews with facility owners/managers, self-reported overall compliance level was 85%.Observed TAPS by Type

Open cigarette displays were the most common types of TAPS, observed in 33% of venues.

Observed Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship Across Cities in Ethiopia, 2022

Source: TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022

Only 52 (3.5%) PoS had outdoor tobacco advertisements. Of these advertisements, 49% were posters, 28.3% were plastic bags, and 11.3% were free-standing umbrellas. Majority (81.5%) of these advertisements were observed at PoS in Semera-Logia.

Cigarette displays were present in 33% of the venues observed. Cigarette displays were more prevalent at permanent kiosks (51%) and regular shops (38.7%) in comparison to merchandise stores (27%), minimarkets (11.9%), and supermarkets (2.1%).

Cigarettes with misleading packaging (such as use of labels like red, gold, green) or terms like full flavor were most commonly displayed in Semera Logia (68.6%), Gambela (58.1%), Adama (42.8%), and Harar (37.4%). The venues with the most misleading packaging were permanent kiosks (40%), merchandise stores (36%), and regular shops (33.4%).

Smokeless or flavored tobacco was only advertised in 0.8% of PoS. Similarly, tobacco products that offer gifts upon purchase were only observed in 0.5% of PoS while multi-pack discounts were only observed in 0.4% of such locations. These advertisements were limited only to Semera-Logia, Gambela, and (to a lesser extent) Addis Ababa.

Compliance With TAPS Ban By Point of Sale

Overall compliance with indoor TAPS bans stood at 60.2%. The least compliant venues with indoor TAPS were permanent kiosks at 40%, while the most compliant venues were supermarkets at 97.9%.

Indoor and Outdoor Compliance with Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship Laws by Point-of-Sale, 2022

Source: TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022

Street vendors were assessed as outdoor spaces, and therefore had no indoors compliance score. Compared to other PoS, street vendors had the lowest outdoor compliance score, at 91%. Some 8.3% of street vendors had outdoor tobacco advertising largely in the form of plastic bags and free-standing umbrellas.

Only 5% of indoor PoS had any tobacco advertising (adverts with tobacco company logos or symbols were found at 8.8% of permanent kiosks) Placement of tobacco products next to children’s products was more common at regular shops (51.9%), minimarkets (50%), and merchandise stores (45.8%) than other PoS. About 69% and 72.5% of the PoS in Semera-Logia and Gambela, respectively, had cigarettes placed near kid-friendly items.

Compliance With TAPS Ban by City

Compliance with TAPS outdoor bans was high across all regions, while compliance with TAPS indoor bans ranged from a high of 82.3% in Addis Ababa to lows of 26.3% in Semera-Logia and 37.1% in Gambela.

Indoor and Outdoor Compliance with Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship Ban by City, 2022

Source: TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022

PoS in Addis Ababa, Jigjiga, and Harar did not generally display cigarettes on counters, near cashiers, or near children’s merchandise. In addition, PoS locations in Addis Ababa largely did not display cigarettes openly at registers or on shelves.

Conversely, PoS locations in Gambela and Semera-Logia mostly displayed tobacco products near children’s products, near cashiers, and openly on shelves. Harar (96.3%), Hawasa (35.9%), and Bahir Dar (33.7%) had the highest number of cigarette packages suggesting flavor.

Article 49 (4) of Proclamation No. 1112/2019 prohibits the sale of single stick cigarettes.

The Proclamation also bans the sale of tobacco products by and to anyone under the age of 21.Single sticks sales

Evidence on compliance with the ban on single stick cigarettes sales in Ethiopia is limited.

In the 2022 TCDI Ethiopia study

, most PoS in ten Ethiopian cities (87.4%) sold single stick cigarettes, with the vast majority being khat shops (95.8%), street vendors (95.7%), minimarkets (94.4%), and permanent kiosks (93.8%). Almost all (99%) of Adama PoS locations sold cigarettes in single sticks. The regions with the fewest PoS locations selling single stick cigarettes were Addis Ababa (51.1%) and Semera-Logia (54.3%).Compliance with Laws Against Single Sticks Cigarettes Sales, 2022

Reported Sales By Point of Sale

Reported Sales By City

Source: TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022

The sale of single sticks is prevalent in many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries.

The sale of single cigarettes at stalls within a 250-meter radius of primary schools is also prevalent across countries.The national tobacco control strategic plan of Ethiopia aims to completely restrict the sale of single stick cigarettes.

According to Ethiopia Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), 61.4% of smokers obtained their cigarettes via single stick sales in 2016. Single stick cigarette sales are problematic for a variety of reasons. Studies around the world have shown that selling single stick cigarettes makes smoking more affordable for the underprivileged and minors who are unable to afford packs with 12-20 cigarettes.Single sticks are cheaper than a full pack of cigarettes and, consequently, make tobacco more affordable to youth and other individuals with limited resources.

Researchers examining youth smoking in Argentina found that the purchase of single cigarettes was more frequent among students from poor schools. The experience from 10 African countries (Burkina Faso, Côte D’ivoire, Ghana, Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Kenya, Nigeria,Togo, and Uganda) indicated that single sticks are readily available, sold and consumed in all 10 capital cities included in the study.Sale to Minors

Only 28.7% of hospitality venues reported that age restrictions are in force, with the highest compliance in minimarkets (61.1%) and lowest in khat shops (16.7%).

Compliance with Laws Against Single Sticks Cigarettes Sales, 2022

Reported Age Restriction by Point of Sale

Reported Age Restriction by City

Source: TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022

Age restrictions were mostly enforced in Addis Ababa (68.5% of PoS locations) and lowest in Bahir Dar (0%). The age of a buyer can be determined by looking at his/her physical appearance and no doubt for any regular person to perceive him as an age of 21.

If it is difficult to determine the age by looking at physical appearance, the directive suggests confirming age by checking his/her identity card. Accordingly, almost all (99.5%) of PoS confirm the age of a buyer by looking at physical appearance, including 94.5% of permanent kiosks. In Bahir Dar city, there is no practice of confirming the age of a buyer (by either checking physical appearance or looking at the ID card).The pictorial health warnings required on cigarette packs by EFDA Proclamation No 1112/2019 are among the largest in the world. Ethiopia ranks 18 out of 206 countries worldwide that have implemented pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs.

Cigarette Package Health Warnings Ranking

The lower the score, the lower the level of compliance

- Average Front/Back Score|

- 0 - 30

- 31 - 40

- 41 - 50

- 51 - 60

- 61 - 70

- 71 - 80

- 81 - 90

- 91 - 100

- No Data

Source: Canadian Cancer Society

Health warnings on tobacco product packages are an effective method of spreading health information, since every tobacco user gets to see the images every day.

Article 11 of the FCTC requires tobacco packages/labels to bear large, clearly visible, and legible health warnings. These warnings, which must be rotated, should cover 50% or more of the tobacco package. The warnings may also take pictorial form. According to the Guidelines to Article 11 of the FCTC, the larger the pictorial health warnings, the greater the impact. In addition, the health warnings should address a range of issues that are tailored to gender, age, or particular groups in the population. The guidelines further recommend that multiple warnings should be in circulation at any given time. The warnings and messages should also be changed from time to time, and plain or standardized packaging should be considered as well. By 2018, pictorial warnings on cigarette packs were in place in 117 countries and jurisdictions worldwide. Sixteen African countries, including Ethiopia, have implemented pictorial health warnings.EFDA Proclamation No 1112/2019

sub-article (I) provides that the picture portion of the warning shall occupy no less than 70% of the front and back side of each principal display area of its packaging and labeling, not counting the space taken up by any border surrounding the health warning.All Cigarette Packets at the Shop Have Pictorial Health Warnings (Which Covers 70% of Front and Back of the Packet) by City, 2022

Source: TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022

In the 2022 TCDI Ethiopia study,

observed compliance with the law on pictorial health warnings varies in select cities in Ethiopia, ranging from a high of 92.8% in Gambela to a low of 3.7% in Harar.Only 48.4% of the PoS in Ethiopia have cigarette packs bearing pictorial health warnings (which cover 70% of front and back of the packets). PoS in the Eastern part of Ethiopia do not generally comply with the requirement for pictorial health warnings on tobacco products – in fact, only 3.7% of PoS in Harar, 4.2% of PoS in Jigjiga, and 9.3% of PoS in Dire Dawa had cigarette packs with pictorial health warnings.

Ethiopia has made remarkable progress in adoption and implementation of tobacco control laws. However, the 2022 TCDI Ethiopia study

indicated several areas for improvement.Strengths and Challenges in Enforcement

Political Commitment

Strength

Strong political commitment at the national level

- There is strong political commitment and leadership at the national level from the EFDA, with focal persons at the regional and zonal levels.

- Federal and regional governments are also undertaking efforts to implement tobacco control policies and enforce tobacco control laws, especially those pertaining to smoke-free public places.

Challenge

Political commitment and stakeholder coordination at regional level

- Limited inter-sectoral collaboration for tobacco control – tobacco control is seen as the responsibility of the health sector. Non-health sectors have inadequate knowledge about existing tobacco control policies and a limited understanding of their roles in tobacco control.

- Inadequate mobilization, engagement, and ownership of community and other stakeholders at the regional level.

- Lack of prioritization of tobacco control policies. Smoke-free areas have been prioritized, but very little effort has been made to tackle TAPS, sales to minors, and other policies.

- Lack of clarity about organizational mandates, especially for TAPS.

- Limited number of partners at the regional level.

Institutional Arrangements

Strength

Strong institutional arrangements to support tobacco control and engage stakeholders at national level

- The National Tobacco Control Coordinating Committee (NTCCC) and Tobacco Control Industry Monitoring and Response Team (TIMR) promote multi-sectoral collaboration.

- Growing body of evidence on tobacco control to facilitate programmatic decisions such as GYTS, GATS, STEPs, EDHS, various studies on illicit trade, enforcement and the TCDI Ethiopia dashboard;

- Technical and financial support from global, regional, and local partners

- Increasing availability of cessation services (such as the 952 toll-free hotline for counseling services)

- Monitoring and evaluation of progress in implementation of tobacco control policies through the Global Tobacco Control Report (GTCR), and clear monitoring and evaluation mechanisms set up by EFDA, especially for smoke-free policy implementation.

- Law enforcers or regulatory bodies working under the EFDA and regional health bureaus have clear enforcement mandates.

Challenge

Inadequate institutional resources to support enforcement

- There is no specific/unique department charged with tobacco control at the federal level. The tobacco control structures at regional and district level are also inadequate.

- Lack of regular impact assessments for all tobacco control laws and policies.

- Lack of sufficient human and financial resources for enforcement due to competing priorities of government agencies. Tobacco taxation revenue is not allocated to tobacco control activities

- Inadequate cessation support, inadequate knowledge and capacity of healthcare workers to offer brief tobacco cessation interventions, and unavailable nicotine replacement therapies.

- The tobacco industry is also promoting breaches of the TAPS ban through distribution of branded materials to tobacco retailers.

Socio-Economiac Factors

Strength

Socioeconomic factors such as culture, societal norms, and religion

Tobacco smoking is not considered as a positive behavior in most cultures and religions in Ethiopia. Combined with education and awareness activities by the government and civil society, this has facilitated the implementation of the smoke-free law and the ban on TAPS.

Challenge

Socioeconomic factors: Culture, societal norms, economy, and religion

- In regions like Gambela, law enforcers face difficulties with engaging local communities because the use of tobacco products is a traditional cultural practice (e.g. Gaya).

- In some areas, khat, which is a gateway drug for tobacco use, is also culturally acceptable.

- Tobacco growing and selling is a source of income/livelihood for some in tobacco growing areas. This causes reluctance to enforce tobacco control laws.

- Insecurity in regions where there is conflict and at certain borders hampers enforcement.

Recommendations

1.

Capacity building for enforcement agencies

The capacity of tobacco control law enforcement officers at national and regional levels should be strengthened. This capacity building effort may include providing adequate financial resources for enforcement, deploying human resources who possess adequate tobacco control expertise, monitoring implementation of tobacco control policies, regularly training officers on tobacco control, highlighting the benefits of tobacco control, and specifying the exact roles and responsibilities of officers.

2.

Awareness creation for the public and relevant stakeholders like owners of hospitality venues and retailers

Concerted efforts are needed to educate and promote awareness among the hospitality industry. For example, venue owners and retailers that sell tobacco products need to be made aware of their obligations under the various tobacco control laws, the benefits of tobacco control, and the dangers of tobacco use. Public awareness should also be intensified on the harms of tobacco use.

3.

Enforcement agencies need to concentrate their efforts on:

- Ethiopia’s eastern cities (Semera-Logia, Jijiga, Harar, Dire Dawa), are vulnerable to the smuggling of various illicit cigarettes, including flavored tobacco products. These cities also have low compliance with TAPS and smoke-free mandates

- Bars/nightclubs, which are the least compliant hospitality venues for smoke-free policies and cigarette displays(such displays are the most prevalent form of TAPS in Ethiopia)

- Khat shops, which are the least compliant in preventing sales of tobacco products to children

- Seizures of tobacco products that are non-compliant with pictorial health warnings requirements

4.

Improve enforcement capacity at the regional level

Regional laws should be adopted, standardized enforcement protocols should be developed for consistent enforcement across regions, and regional coordination mechanisms need to be established.

5.

Institutionalize regular monitoring and evaluation of enforcement activities and compliance with tobacco control policies to provide better data for policy making and implementation.

6.

Strengthen integration and coordination among government stakeholders and civic societies both at federal and regions.

Sources: TCDI Ethiopia Smoke-Free Study, 2022 TCDI Ethiopia TAPS Study, 2022 and EFDA